Content navigation

We are now just days away from the US presidential election, when American voters will choose between Kamala Harris and Donald Trump. The campaign has been extraordinary, marked by Joe Biden’s withdrawal as a candidate, the assassination attempts on Donald Trump and the abandonment of various electoral norms.

For all the drama, though, the election remains finely balanced – especially in the crucial swing states. An election that’s too close to call, then – but what impact will it have on the world’s financial markets?

Surprises from history

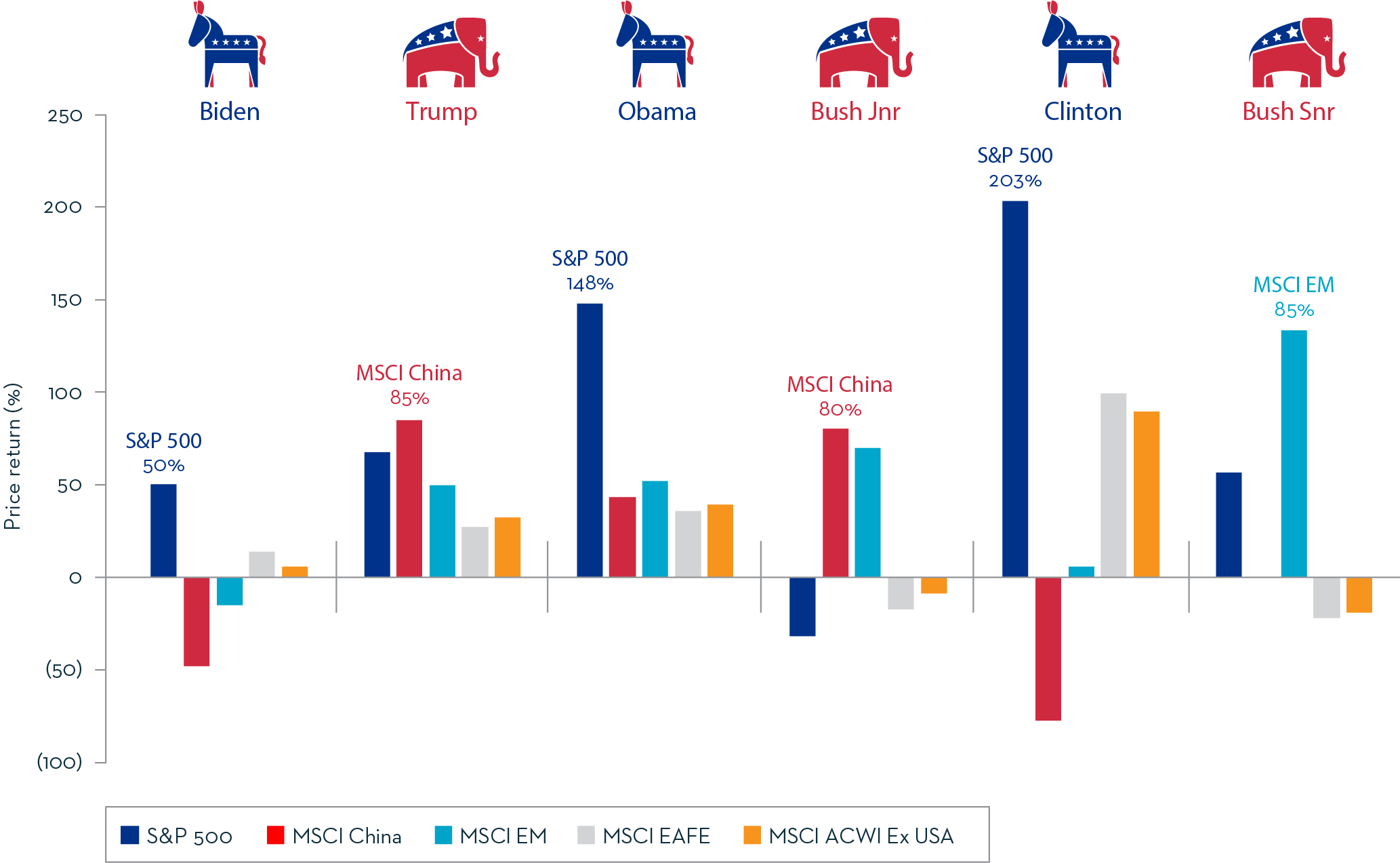

Received wisdom might suggest that wins by the Republicans – the ‘party of business’ – lead to the best outcomes for the US stock market. But history paints a somewhat different picture. Although Donald Trump made great play of the S&P 500’s performance during his administration, the US market underperformed its Chinese counterpart on his watch.

The stock-market outcomes from previous Republican administrations tell a similar story. During the presidency of George W Bush (Junior), both emerging markets and China outperformed the US equity market. And although the Chinese market wasn’t yet established as a destination for global capital, emerging markets also outperformed under George HW Bush (Senior).

By contrast, the US stock market outperformed its global peers under Joe Biden, Barack Obama and Bill Clinton. The table below sets out the performance of major equity indices during the last seven presidential terms.

Over the last 35 years, the S&P 500 has outperformed international equities under Democratic presidents instead of Republicans… but the underlying picture is more complex

Price return of US and international markets in USD(%)

Franklin Templeton and Morningstar as at 2 October 2024 in USD. Market returns for different presidential terms are over the following periods: Joe Biden 1 January 2021 – 30 August 2024, Donald Trump 1 January 2017 – 31 December 2020, Barack Obama 1 January 2009 – 31 December 2016, George W Bush (Junior) 1 January 2001 – 31 December 2008, Bill Clinton 1 January 1993 – 31 December 2000 and George H W Bush (Senior) 1 January 1989 – 31 December 1992. Barack Obama, George W Bush and Bill Clinton all served two terms. Returns for MSCI China not available for George H W Bush presidency.

It would be naïve to argue that these outcomes depended solely on the party affiliation of the president. As we shall see, the US Federal Reserve’s (the Fed’s) independent monetary policy tends to be much more significant for the wider world than whoever occupies the White House.

Nevertheless, US fiscal policy and other government initiatives have played a part in determining the relative performance of US and international equities – as have a range of external events.

-

Despite all the excitement and uncertainty surrounding the election, our focus in the coming months will be on the Fed rather than the White House.

A Republican reversal?

We have noted that emerging market equities outperformed US equities under George HW Bush. A major factor in this was the Brady Plan1, which helped developing countries restructure their debt after a wave of defaults2 – notably in Latin America. The Brady Plan encouraged these countries to implement economic reforms, making their markets more attractive to international investors. In doing so, it accelerated the wave of liberalisation that swept across emerging markets after the end of the Cold War.

Meanwhile, the US economy underwent a recession in 19903, which dampened the performance of its own market even as the potential of emerging markets was unleashed.

The next Republican presidency, that of George W Bush, was also marked by US-led efforts to reform and internationalise emerging markets, in this case China. In December 2001, Bush signed a proclamation granting China permanent normal trading relations with the US. This facilitated China’s entry to the World Trade Organisation and led to increased foreign direct investment.

Throughout Bush Junior’s tenure, China focused on investing in its domestic economy and infrastructure at a time when the US was increasingly preoccupied with the ‘War on Terror’. On top of this, the bursting of the ‘dot-com’ bubble cast a long shadow over the S&P 500’s performance. Its impact was compounded by the global financial crisis of 2008, which entirely erased the recovery the US stock market had made since its trough of 2002.

The period was also characterised by significant technological advancements, including the rollout of broadband, with a surge in demand for metals such as copper. The accompanying commodity boom benefited producers in emerging markets, as did China’s rapid urbanisation.

In some important respects, Donald Trump’s presidency marks a break with his Republican predecessors. Where the Bush presidencies had both focused on engagement with emerging markets and China, Trump took a markedly protectionist stance, characterised by his imposition of heavy trade tariffs on China. But with Beijing pumping in economic support and fiscal stimulus, the Chinese economy proved resilient. Chinese shares were also seen as undervalued3, which helped to boost stock prices in Shanghai, Shenzhen and Hong Kong.

At the same time, we should note that the MSCI ACWI ex US, EAFE and EM indices underperformed the S&P 500 during Trump’s presidency. China aside, non-US stock markets struggled with wider disruptions of trade, the strength of the US economy and dollar, and the very robust performance of US technology stocks.

Democrats – making their own luck?

When we look at the relative strength of the US stock market under the Democrats, we might observe that there’s an element of luck in the timing of events. The S&P 500’s strikingly robust performance under Bill Clinton owed much to his administration’s focus on fiscal discipline, reducing the deficit and promoting technological innovation.

These contributed to economic expansion and in turn led to strong stock-market returns. But it was also under Clinton that the dot-com bubble was allowed to inflate. Bush Junior’s very narrow victory over Al Gore meant that a Republican administration had to absorb the aftermath.

Barack Obama began his two-term presidency in 2009 in the wake of the global financial crisis and the midst of the Great Recession. His swift response, in the form of the Recovery Act, helped to kickstart the longest bull market in US history4.

We might note that Obama’s stimulus packages and the Fed’s programme of quantitative easing can be seen to have done more for the US stock market than the economy itself; growth remained relatively subdued even as shares sustained their long upward march.

The strong performance of the US market under Joe Biden stands in marked contrast to much of the rest of the world, with negative returns from emerging markets – especially China – and subdued returns elsewhere.

The Biden presidency has been characterised by massive external disruptions, including the latter stages of the Covid pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But the US market coped much better than its international peers with the rampant inflation and high interest rates that followed.

The US as global rate-setter

That brings us to a key point. Tighter monetary policy is a hurdle for the US stock market. But high US interest rates and a strong US dollar tend to weigh more heavily on the performance of international markets – and especially emerging market equities.

Here, we should acknowledge the extraordinary dynamism of the US economy, which has allowed it to withstand tighter monetary conditions. After a slight contraction in the first quarter of 2022, the US economy continued to grow robustly even as interest rates rose to reach their highest level in over 20 years5.

During that period, the US growth machine sucked in capital from around the world, attracted by higher yields, and the US equity market has priced itself on that basis. Meanwhile, an increasingly digitalised economy is intrinsically less vulnerable to higher borrowing costs, which have less impact on businesses reliant on software rather than physical assets6. With the Fed having now started to cut interest rates, the stage is set for further domestic dynamism after a period of remarkable resilience.

But the Fed is also the world’s interest-rate setter. The 10-year US Treasury bond is often seen as a benchmark for global interest rates. Higher US yields lure investors away from riskier assets (i.e., those outside the US), even as higher borrowing costs dampen economic growth in countries that lack America’s remarkable dynamism.

Conversely, when US rates and yields fall, they have a significant positive impact on international markets – emerging equity markets especially. So, as we look to the polls on November 5, a key question is this: which candidate’s policies are likely to be more conducive to a sustained regime of lower interest rates?

Contrasts and common ground

A win for Kamala Harris would create some uncertainties. We have scant indication of her views on trade and the economy, for instance. But clearly, a Harris presidency would mean a greater degree of continuity than a Trump one.

In a split with recent precedents, however, a Harris presidency could be more likely to be positive for international markets and emerging markets in particular. That’s because a continuation of Biden-era policies is likely to give the Fed room to bring down interest rates further.

Some of Harris’ policies could weigh on certain sectors of the US stock market. Her anti-monopoly proposals could affect some of the technology giants that have led the market in recent years. Healthcare companies and producers of fossil fuels would also feel pressure from government policies on pricing and the environment, respectively. Against this, the consumer sectors would be likely to benefit from Harris’ proposed tax relief for lower earners.

Under a second Trump presidency, a key concern for global investors would be his proposals for higher tariffs, especially on Chinese goods. These would be likely to have an inflationary effect and could potentially arrest the Fed’s nascent rate-cutting cycle. This would result in renewed strength in the dollar, with the negatives for emerging markets that that entails.

The policies that Trump has outlined would have roughly the opposite effect to Harris’, with support for fossil fuels and big tech at the expense of the consumer, who would be hurt by the higher inflation caused by tariffs.

There are commonalties too. Both candidates look set to increase the US deficit; the Fed appears unalarmed by this. And both are proposing extensive tax cuts, albeit with different targets.

What comes next?

Despite all the excitement and uncertainty surrounding the election, our focus in the coming months will be on the Fed rather than the White House. The winner of the Electoral College is unlikely to be a major factor when the Fed’s Open Markets Committee mulls over what action to take at its November and December meetings. Political rhetoric does not always become reality, and the new president’s policies will take time to feed through into the hard data that informs the Fed’s decisions.

For investors, the worst outcome could be either party winning complete control of the legislature and executive – removing the checks and balances that come with a split. But in recent US history, ‘unified’ government tends to be fleeting; it has occurred in just six of the past sixteen years7

This has important implications. A lack of Congressional support could impede Trump’s programme of tariffs. More broadly, a split Congress would be likely to lead to more ‘horsetrading’ and consensus-building, with, eventually, more moderate outcomes. Either a Harris presidency or a Congressconstrained Trump should leave the Fed room to loosen monetary policy further in the coming months. And from their current elevated levels, US interest rates have a long way to fall.

Lower US rates and, consequently, a weaker US dollar should feed through to lower rates worldwide and growing interest in the potentially higher returns on offer in emerging markets. Lending from foreign banks to emerging-market companies usually rises when lower US rates make such loans more attractive, allowing economic activity to accelerate.

A weaker dollar also tends to raise demand for commodities such as oil and metals, boosting both their prices and the equity markets of the countries that produce them – many of which are emerging markets. For these reasons, falling US rates have historically translated into stronger returns from emerging-market equities, which typically outperform their developed counterparts during rate-cutting cycles.

One exception might be China. The fortunes of the world’s largest emerging market are increasingly dependent on domestic drivers rather than external forces. We are still waiting to see how Beijing’s recent stimulus measures will play out beyond the initial excitement; in the meantime, investors might be best advised to consider China separately from other emerging markets.

Finally, a sustained rate-cutting cycle in the US is also likely to benefit mid-cap stocks in many markets. Mid-cap stocks tend to respond more vigorously to rate cuts than their large-cap peers – not only because they tend to have a greater proportion of floating-rate and shorter-term loans, but because they benefit from the unleashing of animal spirits as investors take heart and allocate away from bigger, safer choices.

We have already seen signs of this in the US, where the stock-market rally has begun to broaden out beyond the mega-cap tech stocks to areas where valuations are less eyewatering. Once the dust from the US presidential race settles, there could be much more of this to come around the world.

Sources

1Source: The Brady Plan was named after U.S Treasury Secretary Nicholas F. Brady. In March 1989 he launched a plan for distressed sovereigns (countries) to restructure unsustainable debts via the issuance of so-called “Brady bonds". Source: International Monetary Fund, 14 December 2023. How the Brady Plan Delivered on Debt Relief. Neil Shenai and Marijn A. Bolhuis

2Source: The ‘LDC’ debt crisis beginning 12 August 1982 was considered a lost decade for Latin American countries. Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, as at History of the Eighties – Chapter 5 The LDC Debt Crisis

3Source: Statista and St Louis Fed as 23 February 2024. Duration of economic recessions in the United States between 1854 and 2024 (in months)

5Source: Statista and St Louis Fed as 30 April 2024. Monthly Federal funds effective rate in the United States from July 1954 to April 2024. Previous time an effective rate of 5.33% was exceeded was February 2001

6Source: The Rise of Intangible Investment and the Transmission of Monetary Policy – Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago (chicagofed.org)

7Source: Party Government Since 1857 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives

Important Information

This information is issued and approved by Martin Currie Investment Management Limited (‘MCIM’), authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. It does not constitute investment advice. Market and currency movements may cause the capital value of shares, and the income from them, to fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you invested.

The information contained in this document has been compiled with considerable care to ensure its accuracy. However, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made to its accuracy or completeness. Martin Currie has procured any research or analysis contained in this document for its own use. It is provided to you only incidentally and any opinions expressed are subject to change without notice.

This document is intended only for a wholesale, institutional or otherwise professional audience. Martin Currie Investment Management Limited does not intend for this document to be issued to any other audience and it should not be made available to any person who does not meet this criteria. Martin Currie accepts no responsibility for dissemination of this document to a person who does not fit this criteria.

The document does not form the basis of, nor should it be relied upon in connection with, any subsequent contract or agreement. It does not constitute, and may not be used for the purpose of, an offer or invitation to subscribe for or otherwise acquire shares in any of the products mentioned.

Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

The views expressed are opinions of the portfolio managers as of the date of this document and are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or of the firm as a whole. These opinions are not intended to be a forecast of future events, research, a guarantee of future results or investment advice.

Please note the information within this report has been produced internally using unaudited data and has not been independently verified. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure its accuracy, no guarantee can be given.

For wholesale investors in Australia:

This material is provided on the basis that you are a wholesale client. MCIM has entered an Intermediary arrangement with Franklin Templeton Australia Limited (ABN 76 004 835 849) (AFSL No. 240827) (FTAL) to facilitate the provision of financial services by MCIM to wholesale investors in Australia. Franklin Templeton Australia Limited is part of Franklin Resources, Inc., and holds an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL No. AFSL240827) issued pursuant to the Corporations Act 2001.

For professional investors in Canada.

This material is intended for residents in, or incorporated in, Canada and are a Permitted Client for the purposes of MI 31-103. The information on this section of the website is not intended for use by any other person, including members of the public.

Martin Currie Inc, incorporated in New York with its registered office at 280 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and having a UK branch registered in Scotland (no SF000300), Head office, 5 Morrison Street, 2nd floor, Edinburgh, EH3 8BH, Tel: +44 (0) 131 229 5252 Fax: +44 (0) 131 222 2532 www.martincurrie.com, operates under the International Adviser Exemption with the Ontario Securities Commission (‘OSC’) and is therefore currently not required to be registered as a portfolio manager for the purposes of MI 31-103. Martin Currie Inc. is also authorised by the UK Financial Conduct Authority.

For the avoidance of doubt, nothing excludes, limits or restricts our obligations to you under the UK Financial Services and Market Act 2000, National Instruments or any other applicable law or regulation.

The opinions and views in this website do not take into account your individual circumstances, objectives, or needs and are not intended to be recommendations of particular financial instruments or strategies to you.

This website does not identify all the risks (direct or indirect) or other considerations which might be material to you when entering any financial transaction. You should consult with your professional advisers before undertaking any investment activity. The information provided on this website should not be treated as advice or a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security or other investment. The information on this website has not been reviewed by any competent regulatory authority.

For professional investors:

In the People’s Republic of China:

This document does not constitute a public offer of the strategy, whether by sale or subscription, in the People’s Republic of China (the “PRC”). These strategies are not being offered or sold directly or indirectly in the PRC to or for the benefit of, legal or natural persons of the PRC.

Further, no legal or natural persons of the PRC may directly or indirectly purchase any of the strategy or any beneficial interest therein without obtaining all prior PRC’s governmental approvals that are required, whether statutorily or otherwise. Persons who come into possession of this document are required by the issuer and its representatives to observe these restrictions.

In Hong Kong:

The contents of this document have not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in Hong Kong. You are advised to exercise caution in relation to the offer. If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this document, you should obtain independent professional advice.

In South Korea:

This document is for information purposes only. It is prepared and presented to provide an introduction to the business of MCIM and its related companies (collectively known as ‘Martin Currie’). This document does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of any offer to invest in any security, fund or other vehicle managed or advised by Martin Currie.

None of the security(ies), fund(s) or vehicle(s) managed by or advised by Martin Currie are registered in South Korea under the Financial Investment Services and Capital Markets Act of Korea and accordingly, none of these instruments nor any interest therein may be offered, sold or delivered, or offered or sold to any person for re-offering or resale, directly or indirectly, in South Korea or to any resident of South Korea except pursuant to applicable laws and regulations of South Korea.

Martin Currie is not registered with or regulated by any regulatory authorities in South Korea.